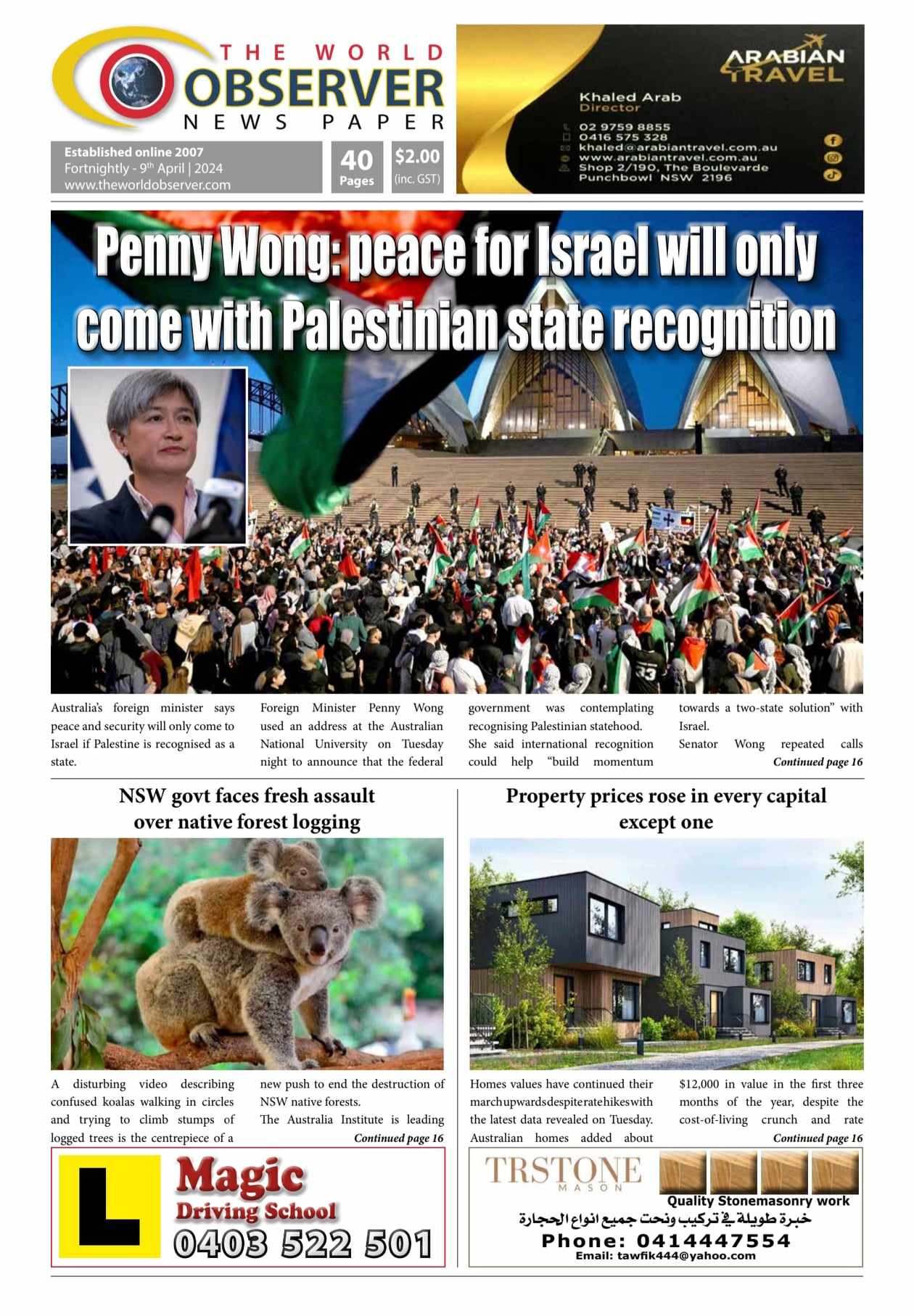

Australians rescuing and caring for injured wildlife have been left to go it alone for so long the ability to continue to save what’s left of native species may end up costing their lives.

If there is a call to evacuate, Bill Waterhouse is intent on staying at his house turned refuge to defend the scores of animals he and his wife have dedicated their lives to helping bounce back from the brink of death.

The New South Wales-based wildlife carer feels he has no choice but to stay because the sites where these animals would be evacuated to were destroyed in last summer’s fires.

An overall lack of funding to rebuild has meant in case of another fire emergency, the 65-year-old – who came out of early retirement to earn money to put towards caring for injured animals – would have nowhere to take them.

“Something like 70 per cent of the bush in our area got burnt. Virtually all of our release sites were burnt out, some never to return,” Mr Waterhouse said.

“Unless some benevolent character, a wealthy ‘Twiggy‘ Forrest or somebody decides to buy some large tracts of land … and establishes them as release sites for animals, we’re just stuck in a rock and a hard place.”

While Mr Waterhouse is adamant he would want to stay to protect the vulnerable critters, he admitted he does not have the necessary water tanks and sprinkler systems installed to defend the refuge from a bushfire.

“We’re really getting desperate,” he said.

After The New Daily spoke to Mr Waterhouse, the Animal Rescue Cooperative agreed to plans to install a sprinkler system, an ember guard as well as tanks and pumps on his property where he runs the Majors Creek Wombat Refuge.

The wildlife carer and casual teacher, who works three days tutoring year 12s, also worries there isn’t enough habitat for rehabilitated animals.

“We need to release them, but we can’t because we’ve got nowhere to let them go,” Mr Waterhouse said.

“We’ve got an animal in every enclosure now. And everyone else has got animals in their enclosures.”

As a consequence, he and his wife have no more space to care for any newly injured wildlife – but they refuse to turn away any animals.

“It’s like a concertina that only half of which works. It’s pushing inwards, but there’s nothing coming out the other end.”

Veronica Morrison, an emergency services worker in East Gippsland who was doing 20-hour shifts during last summer’s bushfire crisis, said there were many wildlife carers in the path of a fire who were ringing up in a panic saying “we’ve got nowhere to take our animals”.

“It was heartbreaking because a lot of animals had to get left behind when the fires were coming through,” she said.

Wildlife carer Rena Gaborov in far East Gippsland does not know where she would shelter the injured wildlife if her Wallabia Wildlife Shelter was threatened by a fire this summer.

Like Mr Waterhouse, she would prefer to stay and defend but isn’t equipped to stop a fire from encroaching on her property.

Ms Gaborov would need to build a concrete bunker for her animals but hasn’t gotten around to it because she’s been too busy reconstructing her wildlife enclosures, most of which were destroyed, along with her home, in a bushfire last year.

A bunker is on the cards but won’t be done by this fire season, making it impossible to know what to do if there was a sudden need to evacuate.

“If I had no time at all, I would just probably jump in a dam and take the animals. I don’t know,” she said.

Even with time to think about an evacuation plan, it’s slim pickings when it comes to finding somewhere to shelter the injured wildlife.

“To just leave them is cruelty”, she said.

Two days before a bushfire ripped through her property last year, Ms Gaborov took the animals to her mother-in-law’s farm and put up temporary fencing to stop them from wandering.

But the bushfire went right through that property. Luckily, Ms Gaborov could see the fire coming and evacuated hours earlier.

“I was just really lucky because someone I knew on the other side of Bairnsdale that wasn’t under threat had an enclosed area that I could put the animals in,” she said.

“If they didn’t have that, I don’t know what we would have done. We would have ended up … in a bedroom or something with all these animals.”

She said she’s always resorted to evacuating the injured wildlife to other private properties but not everyone has that option.

Wildlife carer James Fitzgerald paid to have koala enclosures at a koala researcher’s 60-hectare home, which is about 100 kilometres north of where he lives in the Snowy Mountains of NSW.

“There’s not really much in the way of fallback facilities around,” he said.

“I do think we need to have some level of co-ordination to work out what the plan is. Because climate change is making these events more common.

“Having some sort of idea of how potentially different wildlife groups work together so if one area is under threat, can we move animals into other carers’ facilities and how would that happen?”

The World Observer Media produces a daily online newspaper, a daily Arabic online newspaper and a monthly printed Arabic/English magazine and a weekly printed Arabic/English newspaper.

The World Observer Media’s mission is to entertain and educate all generation from the Ethnic Communities in Australia, who are interested in local, national and foreign information.

The World Observer Media produces a daily online newspaper, a daily Arabic online newspaper and a monthly printed Arabic/English magazine and a weekly printed Arabic/English newspaper.

The World Observer Media’s mission is to entertain and educate all generation from the Ethnic Communities in Australia, who are interested in local, national and foreign information.