It’s taken more than six years to have this 32-minute meeting, 12 minutes longer than the original schedule indicates.

Looking back over the past five decades, face-to-face meetings between China’s and Australia’s top leaders used to be seen as a staple in our diplomatic playbook.

In contrast, yesterday’s one-on-one between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at the G20 summit in Bali was seen as a breakthrough.

Xi said China and Australia should “improve, maintain, and develop” the relationship, which has “encountered some difficulties” in the past few years.

“China-Australia relations have long been at the forefront of China’s relations with developed countries, and they deserve to be cherished by us,” Mr Xi said in his opening remarks.

Albanese described the dialogue as “warm” and “constructive”. He believed both countries took an important step to “moving forward”.

“There are many steps, of course, that we are yet to take… we will cooperate where we can, [and] disagree where we must act in the national interest,” he said.

We didn’t know it at the time, but such meetings came to a muted end at the G20 in Hangzhou in 2016.

Since then, tensions between Canberra and Beijing have festered – a ban on Chinese company Huawei in Australia’s 5G network was imposed by the Turnbull government, while the ABC’s website was blocked by Beijing at the same time.

Australian media outlets published investigations into Beijing’s interference in Australian politics, education and the Chinese community.

The past few years have been marred by hostility over calls for an investigation into the origins of COVID-19, alleged human rights violations, and punitive trade disputes.

That should give Australian politicians a taste of how China’s party-state acts, but as Xi prepares to embark on his third presidential term, our leaders will have to understand the Chinese system on a deeper level.

The Albanese-Xi meeting is grabbing attention, but the dialogue is more symbolic than practical.

It could signal the beginning of a diplomatic thaw, but one of the first questions for Canberra to ponder is how much we really know about Beijing and China’s future under Xi’s rule.

Meeting halfway

Ahead of the highly-anticipated meeting, Albanese spoke positively about dialogue with Xi, saying that even having the meeting with Australia’s largest trading partner was “a successful outcome”.

Xi, however, didn’t give any public hint of his feelings ahead of that dialogue.

The Chinese leader successfully cemented China’s importance on the global stage during his last term, using so-called “war-wolf diplomacy” to seek respect and obedience from the world.

Now he hopes Beijing and Canberra can “meet each other halfway”.

This is a relatively new term in Beijing’s rhetoric, and the meaning of the term is subtle – it is not even featured in China’s national dictionary.

Coined in the Chinese context by the country’s Foreign Ministry, it was first used in relation to the US-China trade war and tensions with Japan.

Now, the term is being applied to Australia, with China’s ambassador to Australia Xiao Qian speaking at a small event in February this year.

Diplomacy is an art of language, and “halfway” is a key word signalling Beijing’s changing approach to diplomatic relations with Canberra.

Walking towards each other and finding a compromise might not satisfy Australia’s initial aims or China’s, but that meeting point should be acceptable to both sides.

The Chinese ambassador seems to be more explicit, as he has specifically called on Australia to “review the past and look into the future, adhere to the principle of mutual respect, equality, and mutual benefit, and make joint efforts to push forward China-Australia relations along the right track”.

Xiao means that when two sides have different positions and interests, it is unrealistic to move towards the same direction.

But even if Beijing is officially willing to set aside controversies or compromise and make concessions, it will not openly admit it in order to save face and maintain its reputation for its Chinese domestic audience.

Still, in the past few months, there has been progress – two face-to-face meetings between foreign ministers, a phone conversation, and the meeting in Bali.

The two countries appear to be taking steps to move closer, but this practice remains at a diplomatic level – there is no concrete substance yet.

Australia is not China’s biggest priority

The most important thing about the meeting was its symbolism – that Xi was willing to meet Albanese.

Whether Australia acknowledges it or not, this dialogue highlights a shift in attitude on Beijing’s part that is more important than the details being negotiated.

But in Xi’s theory of “major country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics”, China is a “major global player”, while Australia is a medium power.

Xi’s posture is condescending.

He met US President Joe Biden right after his arrival in Bali, followed with a dialogue of more than three hours.

But Canberra must wait until he is willing to talk — for 32 minutes.

When the Chinese leader is happy to talk and set the tone for the development of the bilateral relationship, his ministers and envoys would begin to do his will.

This is a potential solution to the impasse between Australia and China on trade and human rights.

For example Beijing, which has been delaying the trial of Australian citizen Cheng Lei, could perhaps order its court to give a verdict swiftly, but it is not certain when she will be able to return to Australia.

And on the trade front, Beijing left the back door open early on — it issued bans and tariffs on the basis of poor quality and dumping, and it will likely lift the bans and tariffs on the basis of improvements.

But there are conditions. Beijing wants to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and wants Australia to continue its one-China policy.

More importantly, Xi wants Australia to see China as a partner, not a rival.

But resetting the relationship overnight seems impossible — it will take time.

The Wang-Wong connection

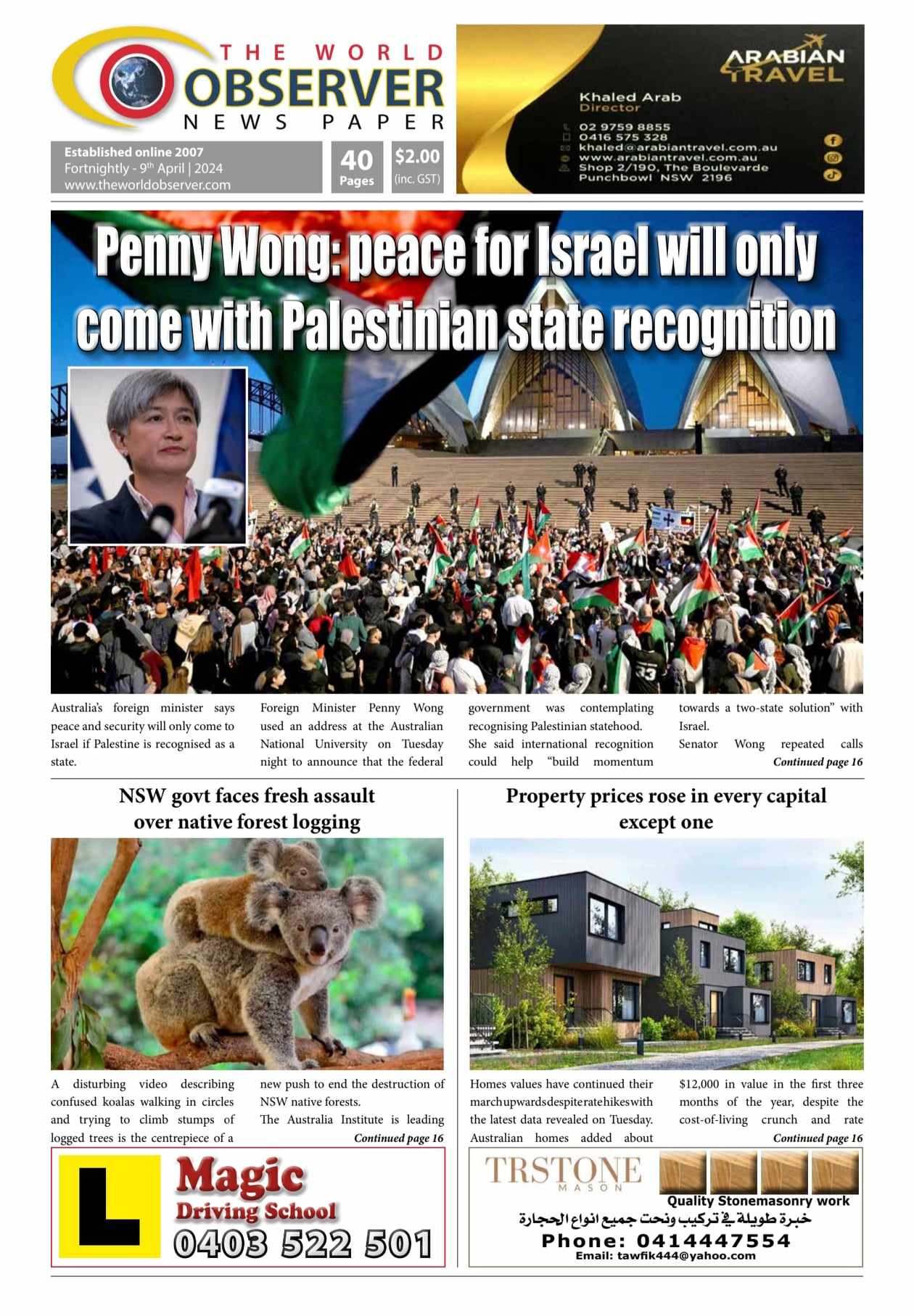

It is significant that Foreign Minister Penny Wong managed to establish dialogue with her counterpart Wang Yi within the first six months of her tenure.

This paved the way for the meeting between the two top leaders and provided a basis for a stabilisation of Australia-China relations – even though things are unlikely to improve in a short term.

Wong has an impressive Chinese name that many Australians overlook: Wong Yingxian, which means being “outstanding and virtuous”.

For the Chinese, Wong’s name and her Chinese ancestry are potentially endearing.

Wang was appointed as a member of the CCP’s Central Politburo at last month’s National Party Congress, which means he will leave his post as foreign minister next March.

However, he will start a whole new political journey as director of the CCP’s Office of the Foreign Affairs Commission.

In China’s party-state system, the position is one of the most powerful representatives in charge of foreign affairs and is responsible for directing the work of the Foreign Ministry.

Chinese culture values good connections and relationships, and foreign ministers having ongoing dialogue is a good foundation for the broader diplomatic relationship.

Wong’s ability to establish ongoing communication and dialogue before Wang’s

departure will undoubtedly set the stage for the Albanese government to handle its relations with Beijing, although it won’t be immediate.

The World Observer Media produces a daily online newspaper, a daily Arabic online newspaper and a monthly printed Arabic/English magazine and a weekly printed Arabic/English newspaper.

The World Observer Media’s mission is to entertain and educate all generation from the Ethnic Communities in Australia, who are interested in local, national and foreign information.

The World Observer Media produces a daily online newspaper, a daily Arabic online newspaper and a monthly printed Arabic/English magazine and a weekly printed Arabic/English newspaper.

The World Observer Media’s mission is to entertain and educate all generation from the Ethnic Communities in Australia, who are interested in local, national and foreign information.