The next time you pick up a bag of spuds from the supermarket or fill up the car with petrol, you can thank a treaty signed 150 years ago for the metric system that underpins daily life.

On May 20, 1875, delegates from 17 countries assembled on a Parisian spring day and signed the Metre Convention, also known as the Treaty of the Metre.

At the time, it wasn’t uncommon for countries, states and even cities to have entirely different ways of measuring distance and mass, hampering trade and holding back progress in science.

To standardise and unify these definitions, the Treaty of the Metre established the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, which initially defined the metre and kilogram.

Over the years, more countries signed the Treaty of the Metre, including Australia in November 1947.

A handful of other units of measurement were also included to form the International System of Units, the basis of the metric system.

But the metre’s inception predates the treaty that bears its name by nearly 100 years.

And its story begins during the French Revolution.

The metre through history

During the late 1700s, revolutionaries shaping the new republic of France shed old traditions bound to royalty and religion.

The Unity Festival in Revolution Square, as depicted by French artist Pierre-Antoine Démachy, was held on August 10, 1793 to promote the values of the French Republic.

This reinvention included creating a new system of measurement.

This system would be available to everyone, and be tied to fundamental properties of nature, “not from the length of the king’s arm, or something that changed over time”, Bruce Warrington, CEO and chief metrologist at the National Measurement Institute, says.

So mathematicians and scientists of the time decreed that the length of a metre — from the Greek word “metron”, meaning “a measure” — was equal to one 10-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the equator through the Paris Observatory.

It fell to a pair of astronomers to calculate this distance, and after seven years, in 1799, they presented their final measurement to the French Academy of Sciences which made a “Metre of the Archives” in the form of a platinum bar.

(It was later found the astronomers were a bit off in their calculations, and the metre as we know it is 0.2 millimetres shorter than it should’ve been.)

The Metre of the Archives and its copies were eventually replaced by around 30 metre bars made of a stable platinum-iridium alloy. They were distributed around the world in the late 1890s, and remained the “standard” metre for decades.

But as science progressed, the definition of the metre changed too.

This change started early last century, when scientists discovered they could measure distances using light.

Light travels in waves. If you know the distance between each wave — called the wavelength, literally the length of the wave — it’s possible to use light “as a very fine ruler”, Dr Warrington says.

And in 1960, the platinum alloy bars were out and a new definition of the metre was introduced.

Pass an electrical current through a lamp filled with krypton gas and the krypton atoms throw off light, including a reddish orange wavelength.

One metre equalled 1,650,763.73 times the wavelength of this specific reddish orange light.

Meanwhile, electronics fabrication kicked off and the scale of manufacturing shrunk to the incredibly tiny. Think transistors in a smartphone integrated circuit, which are only a few billionths of a metre wide.

“So you need rulers that can check for and control the quality of that manufacturing at that level,” Dr Warrington says — something the krypton lamp metre definition could not do.

Since 1960, there’d been a lot of progress made on measuring time accurately with atomic clocks. Their “ticking” is produced by oscillations of radiation emitted when atoms are bathed in laser light.

And they can tick billions of times every second. This new ability to divvy up the second into increasingly tinier slices, coupled with a universal physical constant, the speed of light, redefined the metre.

From 1983, a metre was considered the distance that light travels in a vacuum in 1/299,792,458 of a second (because light travels 299,792,458 metres per second).

This new definition incorporating time and the speed of light opened up new ways of measuring length, Dr Warrington says.

For instance, scientists use it to accurately measure Earth’s distance to the Moon.

“The Apollo astronauts left a kind of fancy mirror on the surface of the Moon, and to this day, you can still fire a laser at that reflector, and time the round trip for the light to go all the way to the Moon and back,” Dr Warrington says.

“And you can turn that into a very careful measurement of the distance between the Earth and the Moon.”

These measurements show the Moon is slowly pulling away from Earth at around 3.8 centimetres each year.

Slow adoption of the metric system

Even as the metre and other units of measurement were being redefined, it was up to each Metre Treaty signatory to adopt the metric system in their own time.

It took Australia more than 20 years after signing the Metre Treaty to officially adopt the metric system when the Metric Conversion Act was passed in 1970.

Other countries have been far slower to go metric. One of the original signatories of the Metre Treaty was … the US.

Today, while day-to-day life in the US tends to use imperial units, the metric system is legally recognised and is “at the core of its civil measurement”, Dr Warrington says.

“So its national standards [for mass and distance] are the kilogram and the metre, just like everybody else’s.”

Even in Australia today you don’t have to look far to see imperial units in, for example, men’s trouser waistbands and television screen size.

One area that still suffers inconsistencies in measurement is in the kitchen, Dr Warrington says.

“I find it slightly frustrating as a professional measurement nerd that an Australian tablespoon is four teaspoons, whereas almost everywhere else in the rest of the world, it’s three teaspoons.

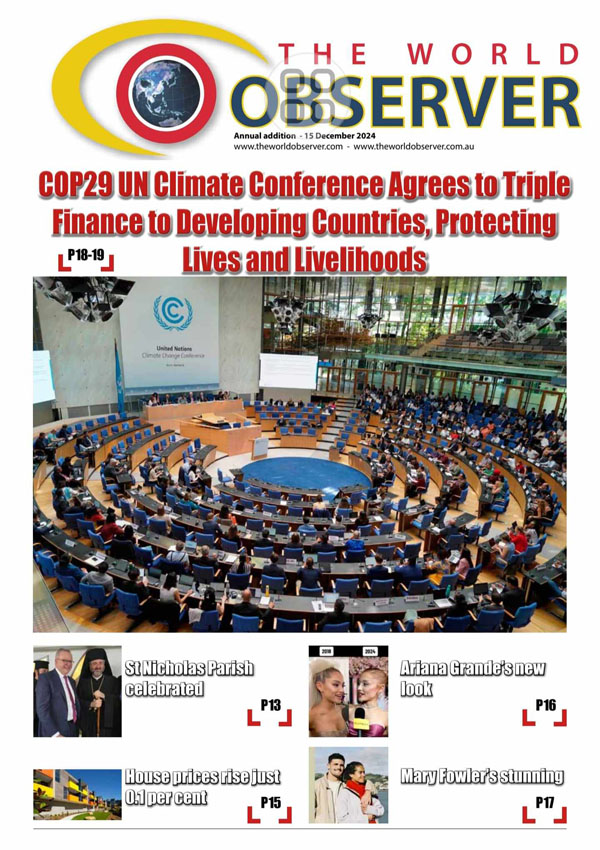

The World Observer Media produces a daily online newspaper, a daily Arabic online newspaper and a monthly printed Arabic/English magazine and a weekly printed Arabic/English newspaper.

The World Observer Media’s mission is to entertain and educate all generation from the Ethnic Communities in Australia, who are interested in local, national and foreign information.

The World Observer Media produces a daily online newspaper, a daily Arabic online newspaper and a monthly printed Arabic/English magazine and a weekly printed Arabic/English newspaper.

The World Observer Media’s mission is to entertain and educate all generation from the Ethnic Communities in Australia, who are interested in local, national and foreign information.